With response times varying from two months to a year, and averaging three or four months, efficient submission of stories to literary journals takes some planning. The delays often seem excessive, but I’m working within the system we have, not the one I think is ideal.

With response times varying from two months to a year, and averaging three or four months, efficient submission of stories to literary journals takes some planning. The delays often seem excessive, but I’m working within the system we have, not the one I think is ideal.

Once a story is complete, I want it working for me right away, until maximum value is extracted. Ideally, I submit a number of stories to a number of journals simultaneously. This is the most efficient route to publication, with the side benefit of eliminating waiting. If I send one story to one journal, I wait for a response while getting annoyed with the delay. If I have three stories in constant circulation, with each story at three different journals at any given time, there’s no way I’ll be able to track that in my head. In a sense, I’m not really waiting for a response if I’ve forgotten about or lost track of the submission. I could track it from my submission log, but I don’t, reducing impatience and annoyance to zero. If publication happens, it’s always a pleasant surprise.

Every story I submit passes through the following stages:

Contests – My chances of winning here are at lottery odds, even worse than regular submissions to journals where the acceptance rates can be well under one percent. But I’m currently keen on contests, so new work goes there first.

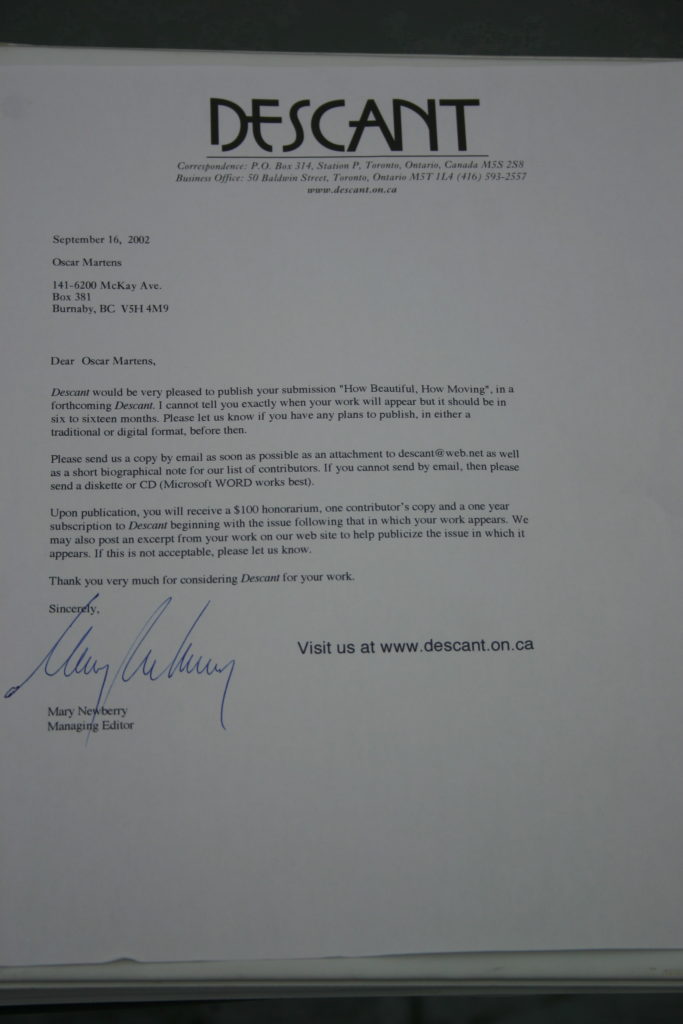

Publication in journals – This is the main show, where most benefits are triggered. In addition to payment, the story advertises my existence to an international readership and directs traffic to my website. Every publication has the potential to increase my Access Copyright payment.

Awards – Once published, my story is eligible for a National Magazine Award and the Journey Prize.

Anthologies – The story can be republished in an anthology. This happened once, by invitation, but I rarely hear about anthologies.

Publication in a collection – Once a number of stories have been published, I can attempt to sell them as a collection. This boosts the payment from the Public Lending Right Program.

Publication on my website – After a story has passed through all these stages, it’s not likely to see any more action, so there’s no harm in posting it on my website.

The order is important. For example, if I put an unpublished story up on my website, some magazines would consider it published, despite the fact that my website is not an online journal. The story would become ineligible for many of the other stages.

Some journals are taking advantage of the Internet to streamline the submission process. Malahat Review recently enabled fiction submissions on their website through Submittable. Many journals have not yet gone paperless, citing fears of viruses that might take out their system. If it’s lack of money, I can understand, but it seems that viruses might be adequately addressed with the latest anti-virus technology, proper backups, and other relevant tech solutions. At this late stage in the digital revolution, I don’t know why any editor would want to be buried in a mountain of paper. Going paperless saves trees, saves space, and saves both parties money on postage. Who is resisting this and why?

Speaking of postage, online submissions have eliminated one of the greatest rip-offs in the history of postal service, the dreaded International Reply Coupon. And speaking of greatest rip-offs, the original Ponzi scheme was based on the arbitrage of IRCs for postage. If you’ve ever submitted overseas, you’ve probably had to buy some of these. Part of the submission package to a non-digital journal includes a Self-Addressed Stamped Envelope (SASE) because most journals can’t afford charges related to the return of manuscripts. This works fine in your own country, but when you want to submit internationally, your domestic postage isn’t going to work. This seems pretty obvious, but judging from the numerous warnings to submitters on the submission pages of many journals, this still happens often. I used IRCs in the past, but then I discovered that Canadians can purchase American postage directly from the USPS online. It’s a good thing, too, because Canada Post now charges $6.50 for an IRC, which will purchase enough postage in a foreign country to return one standard-sized letter. In the case of a Canadian sending something to the US, you’d be spending $6.50 CAD on something that was worth $1.15 USD. Perhaps realizing that online sales of stamps made IRCs unnecessary, the US discontinued the issuance of out-going IRCs in 2013.

In recent years, I’ve noticed that SASE protocols at some journals are breaking down. Often, even if I have sent enough postage to have my entire manuscript returned, all I get is my cover letter or a rejection slip. If I’m spending $2.00 on return postage, I want my damn manuscript back, thank you very much.

If I were to remake the submission universe, I would insist on the full use of digital technology. In addition, submissions would be limited to 300 words. If editorial offices are critically overloaded and understaffed, I think this is a fair compromise. I don’t expect the first reader to read all 3500 words of my story. If I don’t have you by the first page, you’re not going to fall in love with what comes next. Move on and save us both some time. What are the odds on an editor hating the first page and changing her mind by the end of the story? Vanishingly small, I’m guessing. This is also the standard I use when reading. As a writer, if you can’t make the first page interesting, you’ve shown considerable contempt for the reader. I will not wade through a chapter or two to see if it improves at some point. I won’t finish a book out of obligation or some strange compulsion to finish what I started.

It’s ridiculous that any journals still insist that submissions must be on paper. Is it because it saves the editor the trouble and expense of printing it out? An editor either has to adapt to the fact that much reading is done on electronic technology now, and if they insist on paper, then they need to eat that expense. Is it that they are worried about “viruses?” I remember I used to hear that a lot when I was submitting stories in the 1990s. Easily solved with either anit-virus software which is cheap, or submission via webform which eliminates direct email altogether.

As for the unacceptable wait times that journals often subject writers to, I also have never, ever bought the “overloaded staff” argument. As Mr. Martens implies in his last paragraph, there are very efficient and accurate ways of assessing submissions which don’t involve reading every word of every page of absolutely everything that gets submitted. As the great and cranky Samuel Johnson once said when someone questioned him about why he didn’t finish a certain book, “when I take up the end of a web, and find it packthread, I do not expect, by looking further, to find embroidery.”

I feel strongly that journals not only have to adapt, but also that if they don’t they need to be concerned in the evolutionary sense of what happens when a species doesn’t adapt. There are other journals which can publish a work in less than a year. A writer can publish his own damn work online. And so on … I just checked my watch, and it’s the 21st century!

I understand your anger. The “overloaded” argument may be true, but the sorry state of response times may also be a result of the huge power imbalance between writers who want to get their work published and editors who decide what appears in print. There is usually some payment with Canadian journals, but many would write for free just for the publication credit. Journal editors can take a year to respond because they can. That’s what happens when rejected stories outnumber accepted ones by 100 to 1.